Unless you have been living under a rock you have probably noticed that the government has mandated that the gasoline you are pumping into your car these days has Ethanol in it now. You have probably also heard that it is good for farmers and the environment but lets look at all those factors and one more…

Is there a link between Ethanol and Inflation?

These days Ethanol is the hot topic in many different circles including conservation, farming, energy, and even in investment circles.

Ethanol is the latest additive to be used in gasoline. Throughout the years several different additives have been added to gasoline. Back in the 1940s tetraethyl lead was added to help boost the octane of gasoline creating the first “Ethyl” gasoline. But by the mid-1970’s it was found that a thin coating of Lead dust was covering the earth from the exhaust fumes. And since lead was toxic to animals and especially to humans, lead was banned from gasoline in 1978. But refineries needed a new additive to boost octane. So, they began adding methyl tertiary-butyl ether (MTBE) instead. Which was the first “unleaded” gasoline.

Unfortunately, MTBE was found to cause cancer and as it leaked from underground gasoline storage tanks it found its way into local water supplies and so instead of dying of lead poisoning people began getting cancer. So once again the government mandated a change. The result of all this is that ethanol is now replacing MTBE in gasoline.

Talking about ethanol is good politics. Imagine a single topic where you can fight cancer, battle pollution, boost the economy, fight foreign oil dependence and help farmers all at once and you have Ethanol! And to top it all off Ethanol is renewable. So what’s the problem?

First of all, there is some debate as to whether leaking ethanol is any better than leaking lead or leaking MTBE. So ethanol might not be much of a solution to either cancer or pollution.

Secondly, there is a heated debate about the economics of producing ethanol i.e. whether it would be economically viable without government subsidies.

Thirdly, the energy content of ethanol is approximately two-thirds that of gasoline by volume. So it takes more ethanol to run your car than gasoline. Put another way, the more ethanol you burn the worse your mileage (mpg) will be. Ethanol is usually used in a blend known as E10, which is 10 percent ethanol and 90 percent gasoline. At levels higher than this your car needs to be readjusted to account for the lower energy content.

And since ethanol is made by turning starch or sugar from plants into alcohol it needs to be distilled and distillation requires heat. Heat requires energy, so there is a debate as to whether ethanol actually produces more energy than it requires to make it. So although it might reduce foreign oil needs it will increase the total number of gallons of gas burned and require more energy to produce.

It is currently taking about 6% of the US corn crop to make 90% of all US ethanol. But ethanol is only currently 10% of the fuel. So the question arises can we use 12% of all the corn and double production to 20% of our fuel? Or can we use 24% of all corn to produce 40% of our fuel?

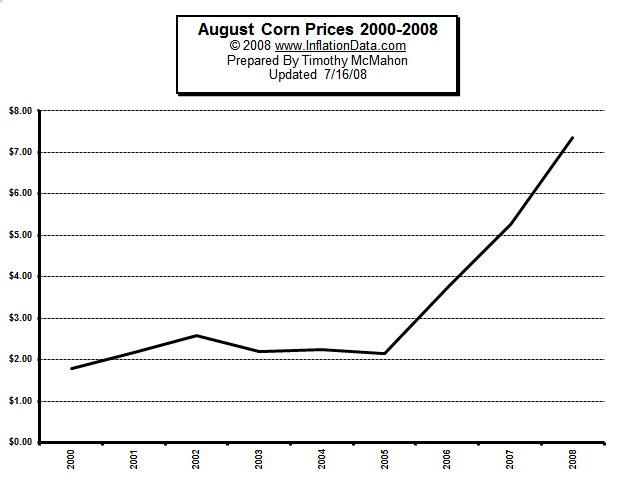

Since the government mandated the change in gasoline additives from MTBE to Ethanol, Corn prices have almost doubled, going from just over $2.00 a bushel to almost $3.50. So imagine where the price of corn would go if we used 40% of the available supply in making ethanol.

In reality, corn-derived ethanol won’t make a noticeable dent in our overall oil usage even though we grow more corn than anyone in the world. An Energy Department official said 18 billion gallons was the maximum amount of corn ethanol that we could be produced annually. Which is only a small fraction of our 140 billion-a-year oil habit. And currently we are only producing something like 25 million gallons of ethanol.

So if producing 25 million gallons of ethanol drives the price of corn up to $3.50 a bushel how much would corn cost if farmers sold enough of it to make 18 billion gallons?

What effect will higher corn prices have on other products that use corn as a feedstock? Corn goes into much more than just corn on the cob and tortillas. In reality, almost every farm raised animal in the United States is force-fed corn. Everything from Beef to chicken, to pork and even salmon! It takes over ten pounds of corn to raise one pound of beef. And meat isn’t all corn is used in everything from adhesives to crayons, peanut butter and yogurt. As a matter of fact corn is already the nation’s no. 1 crop. Of the 10,000 items in a typical grocery store 2,500 of them use corn in some fashion or other.

So how much will prices of everything else inflate if the price of corn doubles? Or triples? Or even Quadruples as more and more corn is used for fuel. The only mitigating factor is that as prices for corn rises the government’s subsidy to corn farmers will decrease. Last year the government spent nearly 8.9 Billion dollars in corn subsidies but next year if current prices continue that could fall to $2 Billion.

So although the government may save almost $7 Billion consumers will most likely end up paying that and more in increased costs for all those 2,500 corn related products.

That brings us back to the question of the energy it takes to produce ethanol. One of the biggest energy components of producing Corn is nitrogen fertilizer and one of the biggest components of Nitrogen fertilizer is natural gas. Plus it requires a great deal of electricity to actually make the ethanol. Back in the 1970’s it actually took more energy to grow and refine the ethanol than you got from it . Today due to increases in efficiency that is no longer the case.

So ethanol is a complex proposition that uses a significant amount of energy to produce and could have a major impact on the price of a wide variety of other products competing for the corn.

However although the price of corn has been rising in the short term since 2000 on a historical basis (over the longer term) corn is actually still very cheap in inflation adjusted terms. See The Inflation adjusted Price of Corn for more details.[ad#CaseyResearch]