Mexico holds an estimated 545 trillion cubic feet of technically recoverable shale gas and 13 billion barrels of shale oil, but progress in developing those resources has been slow.

The obstacles to kick-starting Mexico’s shale industry have dampened the once lively enthusiasm surrounding Mexico’s historic energy reform. Mexico passed legislation last year that opened up the country’s oil and gas sector to private investment, ending a 75-year monopoly by state-owned Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex).

But the secondary laws that the government must pass to actually implement the legal framework for oil and gas development are proving much more contentious.

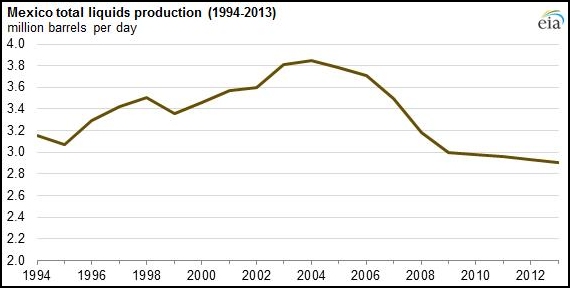

Political disputes over what could be 21 separate laws have thus far delayed passage, threatening to push back Mexican President Enirque Pena Nieto’s goal of producing 3 million barrels of oil per day by 2018. That would be roughly a 25 percent increase from the current output level of 2.4 million barrels per day, but it is looking increasingly difficult to achieve.

“We can increase, of course, but not enough to arrive at 3 million [b/d],” Fluvio Ruiz Alarcon, an independent board member at Pemex, told Platts on June 24 at a Wilson Center event in Washington, D.C. “I’m sure we’re going to produce over 3 million [b/d] but not by 2018. Maybe 2020, but not before,” he added.

In order to access the potentially abundant oil and gas from Mexican shale, the government will need to rely upon the private sector. Under the energy reform, Pemex is given first refusal over any projects – meaning that it can keep the assets it really wants, but allows the rest to go to bidding for private companies. Pemex will likely stick with its wells that are already producing, and leave drilling new shale wells to incoming private companies.

However, many areas in the Burgos Basin – which lies just south of the rich Eagle Ford formation in Texas – are suffering from intense gang violence. Bloomberg News reported on the conditions in Tamaulipas, a state in eastern Mexico, which at times resembles a “war zone.” A power vacuum left over by the arrest of the leaders of the Zetas and Gulf Cartels last year has the eastern coast dealing with heightened violence – shootings along highways and burned down buildings are commonplace as rival drug gangs jockey for territory.

Further north, shootings and kidnappings plague Highway 2, which runs parallel to the border with the United States.

The violence poses an immediate threat to the oil companies working there. The Mexican Army is now escorting workers of Weatherford International, an oilfield services firm, to and from their drill sites after a drug gang shot up a hotel where the workers were staying.

Aside from violence, theft of oil and gas by drug cartels poses another threat to companies. In 2013, Mexican gangs stole around $790 million worth of fuel, which is siphoned off from pipelines and smuggled.

Perhaps more importantly, the violence will undermine Mexico’s attempts to boost oil production over the longer term. The Mexican government doesn’t believe that Pemex will be able to increase production. The state-owned company’s goal is to merely keep production steady as wells age and decline. Instead, the government will be relying upon the private sector. Over the next four years, the government expects 500,000 barrels per day to come from non-Pemex sources.

But that goal will prove elusive if independent oil and gas companies are scared off by violence.

“It does raise the cost of doing business when you have to face the threats of kidnapping and extortion,” Duncan Wood, director of the Mexico Institute at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, told Bloomberg.

If Mexico is to achieve its goal of reviving oil production, which has declined by more than one-third over the last decade, it will not only need to get the legal framework right, but the government will also need to ensure drug violence drops to a level that doesn’t scare off private oil and gas companies.

By Nicholas Cunningham of Oilprice.com