To say that the past year has been an extraordinary period for the global oil market would be an understatement. Entering into 2020, oil was still feeling the impact of the late 2019 drone attack by the Yemeni Houthi movement, on a Saudi Aramco oil processing facility. In early 2020, oil prices were also highly volatile in the aftermath of the killing of Iran’s Qasem Soleimani and then Saudi Arabia and Russia started a price war to drive oil prices down in an effort to put U.S. shale oil producers out of business.

To say that the past year has been an extraordinary period for the global oil market would be an understatement. Entering into 2020, oil was still feeling the impact of the late 2019 drone attack by the Yemeni Houthi movement, on a Saudi Aramco oil processing facility. In early 2020, oil prices were also highly volatile in the aftermath of the killing of Iran’s Qasem Soleimani and then Saudi Arabia and Russia started a price war to drive oil prices down in an effort to put U.S. shale oil producers out of business.

And then the global COVID-19 pandemic created a new reality for oil demand as hundreds of millions of people across the world no longer needed to fill up their cars and aviation travel was all but limited to cargo flights. The price of oil even dipped into negative territory for the first time in history as refiners ran out of clients to sell oil and places to store it.

Shell Acknowledges ‘Significant Uncertainty’

Before exploring the “big picture” of how oil demand impacts the foreign exchange rate of currencies tied to oil, let’s explore an individual company. The most recent oil giant to report earnings (July 30) is the global giant Royal Dutch Shell.

The oil giant reported its first quarterly loss since the end of 2015 as global demand for oil, as expected, was hard hit from the COVID-19 pandemic. Just months prior, the company slashed its dividend payout to investors for the first time in eighty years.

Regarding future oil demand, Jessica Uhl, Shell’s chief financial officer, said “There remains continued significant uncertainty in terms of how the pandemic will play out, we’re seeing a lot of starting and stopping around the world, that impacts our assets, our supply chains”

Inverse Correlation: United States Dollar

The U.S. dollar is inversely correlated to oil demand, in part due to Crude and Brent oil benchmarks being listed in dollars. So when the value of the U.S. dollar changes due to external factors, the price of oil would need to move accordingly to offset the difference i.e. when the U.S. dollar is strong, you need fewer U.S. dollars to buy a barrel of oil. When the U.S. dollar is weak, the price of oil is higher in dollar terms.

But according to at least one expert, the case can be made that the U.S. dollar doesn’t directly interact with oil demand. Rather, changes in oil demand impact other factors that in return impact the U.S. dollar exchange rates versus European currencies.

PetroCurrency

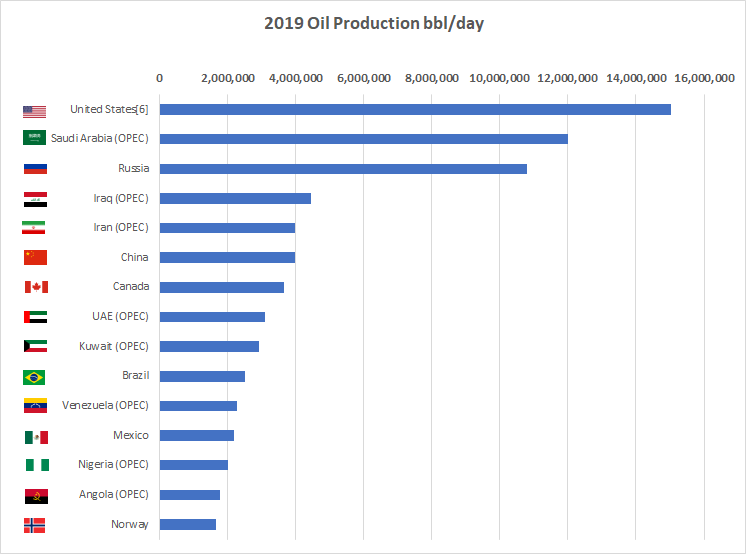

“Petrocurrency” or (more commonly) “petrodollars” is a popular shorthand for revenues from petroleum exports, mainly from the OPEC members plus Russia and Norway. During periods of historically expensive oil, the associated financial flows can reach hundreds of billions of dollars per year.

Direct Correlation: Russian Ruble

The Russian ruble is a notable example of a petrocurrency since energy exports represent more than 70% of the country’s exports. Other countries outside OPEC that rely heavily on oil exports are Canada (Canadian dollar), Norway (krone), and Brazil (real).

Russia is an oil-producing behemoth although it isn’t an official member of the powerful OPEC consortium. In fact, the two sides underwent a painful breakup in March when Moscow identified an opportunity to crush U.S. shale companies.

Russia felt that rock-bottom oil prices would force many U.S. shale companies out of business, especially those with unsustainable levels of debt at the best of times.

The problem is some close observers felt that Moscow’s strategy didn’t consider the consequences on its own currency and economy. But this may have been by design as Russian oil companies merely have to outlast its global rivals amid low oil prices.

The impact on the Russian ruble was evident from day one. The national currency collapsed almost 10% immediately following the country’s breakup with OPEC. It’s not so much that demand changed overnight, rather the supply of oil as Saudi Arabia pledged to flood the market.

Of course, low oil demand and sales also translates to a weaker ruble. Low oil demand translates to lower oil exports and revenue for the Russian government. If the price of a country’s most prized asset goes down, this represents a trade deterioration and the currency by default will be negatively impacted.

Gulf Nations Peg Their Currencies

Multiple gulf nations, including Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates all maintain a currency peg or manage a fixed exchange rate with the U.S. dollar or a basket of currencies.

As an example, 3.6725 United Arab Emirates dirhams can always be exchanged for $1.00 U.S. dollar. In other words, a fixed amount of one currency will always be exchangeable for one U.S. dollar.

But when oil demand and prices are down, these countries need to tap their cash reserves and buy their local currency for the peg to remain within its normalized range.

These oil-pegged currencies would come under significant pressure when a country can’t collect enough oil revenue due to the low demand to fund its day-to-day operations. In this case, the peg could come under pressure, or even break.

Other Factors Affecting the Oil Price

At the end of April, the price for a barrel of West Texas Intermediate crude oil to be delivered in May dropped into negative territory. At that point, Senators from energy-producing states encouraged President Trump to impose tariffs on oil imports. They hoped tariffs would artificially prop up crude prices, and bail out U.S. oil companies. Previously, when Trump proposed tariffs on China as a negotiating tactic the media was up in arms and accused him of all sorts of terrible things. This time he pursued more diplomatic means and eventually got Saudi Arabia and Russia to halt their price war by agreeing to slash production by 9.7 million barrels a day.

You might also like:

- Oil, Petrodollars and Gold

- Saudi Arabia’s Oil Price War Is Backfiring

- How Can Oil Be Worth Less than Nothing?

- So Long, US Dollar As World’s Reserve Currency