The Permian Basin is a sedimentary basin primarily located in West Texas and Southeastern New Mexico. It is named “Permian” because it has one of the world’s thickest deposits of rocks from the Permian geologic period. The Permian Basin is the largest petroleum-producing area in the United States and has produced a cumulative 28.9 billion barrels of oil and 75 trillion cu ft. of gas. Currently, nearly 2 million barrels of oil per day are being pumped from the basin. Advances in hydrocarbon recovery such as horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (fracking) have expanded production into unconventional, tight oil shales which up until fairly recently were unrecoverable. Prior to these advances, all the talk was about “Peak Oil” and that we would run out of recoverable oil. And then along came horizontal drilling and fracking and we are suddenly awash in oil and natural gas. But is it all about to come to a screeching halt as Permian oil production peaks? In the following article about Permian Basin Productivity Nick Cunningham of Oilprice.com looks at where Permian productivity is headed now. ~Tim McMahon, editor

Has Permian Productivity Peaked?

The U.S. shale industry might have just received a huge windfall with the nine-month extension of the OPEC cuts. Shale output was already expected to come roaring back this year, but the extension of the cuts provides even more room in the market for shale drillers to step into.

The sky is the limit, it seems. However, there are growing signs that the U.S. shale industry could be reaching the end of the low-hanging fruit. Or, more specifically, drilling costs are starting to rise and the enormous leaps in production that can be obtained by simply adding more rigs also appears to be running into some trouble.

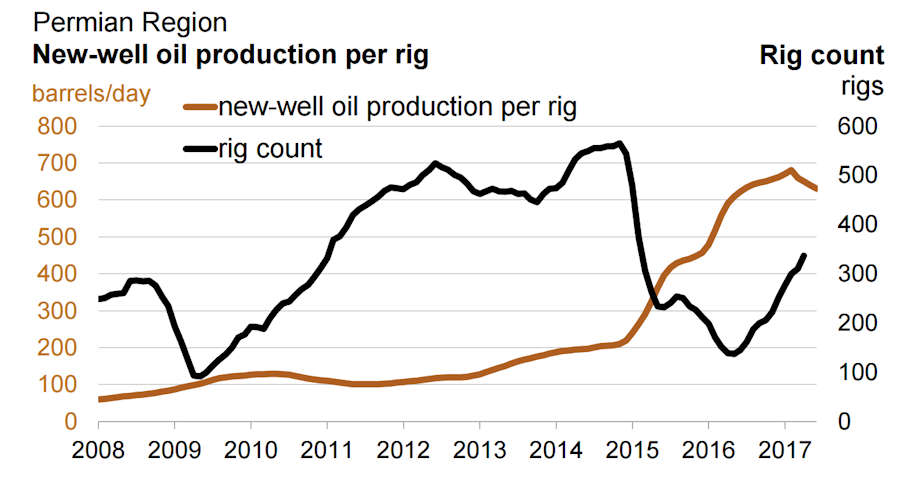

According to the EIA’s Drilling Productivity Report, productivity (as opposed to absolute production) is set to fall next month in the Permian Basin. In other words, the average rig will only be able to produce an estimated 630 barrels per day of initial production from a new well, down 10 b/d from the 640 b/d that such a rig might have produced in May. That is convoluted way of saying that the ever-increasing returns on throwing more rigs at the problem might be hitting a ceiling.

This is a very notable development – it is the first time that the EIA predicts falling well productivity per rig since it began tracking the data several years ago. Still, because the rig count has increased so much, there will still be more production coming out of the Permian. It’s just that as drillers gobble up all the best spots to drill, it will become more and more difficult to find easy pickings.

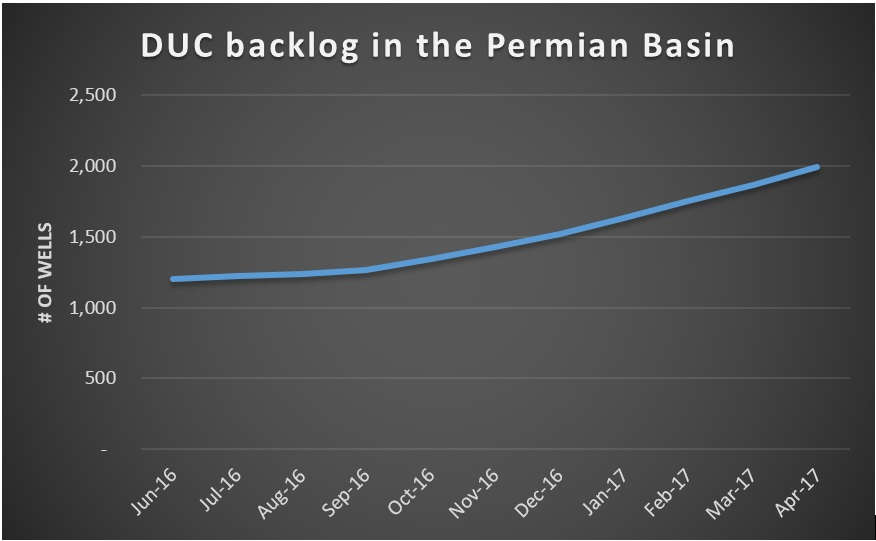

Moreover, simply drilling the wells is only one part of the equation. As Collin Eaton of Fuel Fix notes, companies are drilling wells at a faster pace than contractors can frac them. The shortage of completion crews means that the backlog of drilled but uncompleted wells (DUCs) has shot up over the past year, rising by more than 60 percent to 1,995 in April 2017 from a year earlier.

The strain on contractors means that drilling costs will also rise. Oilfield service companies bore the brunt of the market downturn over the past three years, forced to slash their rates because of the lack of work. Oil producers have consistently and repeatedly boasted about their “efficiency gains,” but much of the cost-savings came from soaking service companies.

That could be at an end. The rise in drilling activity means that oilfield service companies finally have more leverage to hike their prices. The results could be an upswing in costs for producers. Service costs could jump by 20 percent this year, according to an estimate from S&P Global Platts.

But it isn’t all rosy for service companies either. Fuel Fix notes that they have to rebuild their rig fleets after scrapping so many during the last few years. Also, finding enough people to return to work after savagely cutting payrolls will be a challenge.

Overall, however, production is still expected to increase. Generous financing from Wall Street will ensure that capital is not a limiting factor. Consequently, the shale industry will continue to shower West Texas with money, rigs and people. Oil will flow in larger volumes this year and probably next year, barring another downturn. The Permian, for instance, is still expected to add more than 70,000 bpd of additional output between May and June.

Also, OPEC’s determination to prevent another downturn in prices provides some certainty to shale drillers. OPEC is erasing some of the risk for drillers to deploy resources in the Permian. On an annual basis, the EIA estimates that U.S. oil production will average 9.3 million barrels per day (mb/d) in 2017 and a staggering 10.0 mb/d in 2018.

But if well productivity has peaked, the marginal barrel will be a bit trickier to produce next year than it was in, say, late 2016.

This article originally appeared here and has been reprinted by permission.